May (6) 7-8, 2015

Walter Bortz, Stanford University

Leonard Hayflick, University of California, San Francisco

Christopher Jarzynski, University of Maryland, College Park

Robert Laughlin, Stanford University

Arnold Levine, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton

Herbert Levine, Rice University

James L. Smith, Los Alamos National Laboratory

Workshop Synopsis

Biological aging is characterized by loss of structural integrity and functional decline with time. It is generally believed that these changes occur gradually with age, leading to the eventual death of the organism. Engineered physical systems also change as time passes, again losing structural integrity and eventually failing to perform their designed function. This workshop will explore the extent to which general ideas regarding these processes can be applied to both living and nonliving systems.

There have been many proposals regarding the underlying mechanisms of biological aging, most of which focus on a single molecular process. For example, much work has gone into the issue of telomere shortening as a very specific driver of cellular senescence. However, much of this work begs the central question of whether aging is an inevitable consequence of the physical and chemical processes that take place during life or alternatively whether it is a modifiable consequence of a genetic and/or epigenetic program that is being executed by the cells. Most engineered systems fail not because of prior programmed deterioration of its parts, but because of the natural physical processes that take place when complex systems interact with each other. Are living systems similar? This is what we hope to address.

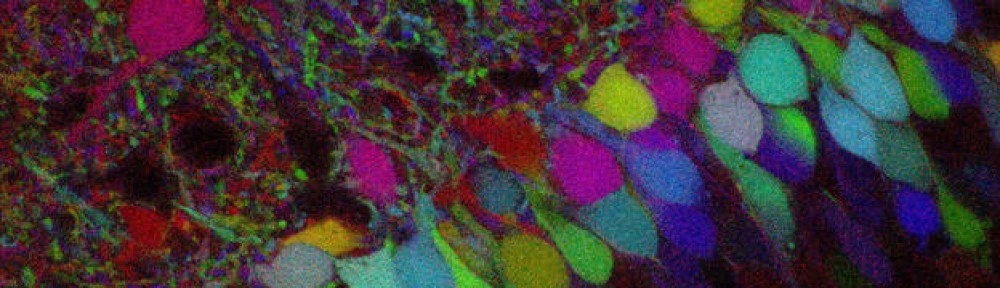

There are several types of aging processes that take place in physical systems. Erosion, corrosion, and structural defect formation are some of the mechanisms contributing to diminished structural integrity, decrease in fidelity and eventual failure of physical devices. Different systems are subject to different mixes of some of these fundamental mechanisms. In living systems, different parts of an organism age differently. For example, the immune system, the skin, and other organs subject to continuous cell renewal, are believed to age due to diminishing cell proliferative capacity. The intracellular mechanisms responsible for the reduction of the proliferative potential of the cells comprising the tissue are not well understood, although many “theories” exist of how such reduction could be brought by the physical and chemical processes taking place in a cell. On the other hand the knee of an animal ages in a different manner. In this case the friction brought by continuous use leads to wear of the cartilage and it gradually becomes harder and harder to use as a joint. In the first example of aging the organs become more susceptible with time to various diseases and eventually lead to disease related death. In the second case the animal cannot compete with its predators and gets consumed by them.

As their parts fail, biological and mechanical systems can and often are repaired. However, the repair process is also by its nature prone to errors, and cannot keep up indefinitely – how many cars from the 1950’s are still operational? This seems to be true both at the individual level and at the species level. But, if we consider life as a whole, evolution seems to have defied this fundamental limitation and life on Earth has been flourishing for most of the history of the planet. Is this just a question of our limited experience with life or will evolution always find a viable strategy.

In this workshop that will take place May (6) 7–8, 2015 at The Hyatt Regency Tysons Corner in Northern Virginia, approximately 25 scientists representing Physics, Material Science, and Biology will discuss the principles and processes underlying aging in living and nonliving system, the similarities and differences between living and nonliving systems and their repair and failure. The workshop participants will discuss what is the relation between non-equilibrium thermodynamics and aging, is there a role for information theory in describing the aging process and how is this information preserved in life as a whole, and finally are there lessons for robust technology development that we can learn from living systems. We do not expect answers to emerge from the workshop, but instead wish to understand how to generate research plans that will in the coming years address these fundamental issues.

Workshop Co-funders:

The Physics of Living Systems Program at the National Science Foundation and the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research

Workshop Administrator

Sara Bradley